The celebration of Pacific/Asian American Heritage at the government level first began in 1977 when U.S. representatives Norman Y. Mineta and Frank Horton launched legislation to create Pacific/Asian American Heritage Week.

In Washington State, May was officially recognized as Asian Pacific American Heritage Month in 2000 by the Washington Legislature. In 2021, both U.S. President Joe Biden and Washington Governor Jay Inslee proclaimed the month of May to be Asian American Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month (AANHPI).

A 2019 report prepared for the Washington State Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs found that 12.3% of Washingtonians identify as AANHPI (alone or in combination). In Clark County, Asian, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders make up 5.39% of the population. In Cowlitz County, ANHPI individuals constitute 1.48% of the overall population and 1.87% in Wahkiakum County.

In Washington, AANHPI individuals have a long and storied history. Originally Chinese populations were drawn to migrate to Washington by news of the Gold Rush and drawn way from their home country due to the civil unrest during the Taiping Rebellion. During the late 1800s, Chinese immigrants were working on railroads, logging, mining and in salmon canneries.

When Hawai’i was annexed in 1898, many Japanese immigrants travelled to the Pacific Northwest to work in logging, the fishing industry and on railroads. In 1898, America acquired the Philippines in the Spanish-American War, which led to an influx of Filipinos to the Pacific Northwest.

While Asian Americans and Native Hawaiians contributed to the prosperity of the Washington economy, their communities often faced adversity. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States. The act was not repealed until 1943. The 1924 National Origins Act restricted Asian immigration even further.

In 1942, U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ordered the internment of individuals of Japanese ancestry. The wrongful internment spanned four years and affected the lives approximately 120,000 people—the majority of whom were American citizens. No interned Japanese Americans were ever found guilty of espionage. It would not be until 1988 when Congress would issue an apology and reparations to as part of the Civil Liberties Act.

After World War II, sentiments on Asian immigration began to shift. During and after the civil rights movement, members of AANHPI populations blazed their way to new successes and greater political representation.

In Washington State, the population of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders grew 34.3% between 2010 and 2019.

In the 2019 report, wage data reflected that workers with Asian Indian, Chinese, Japanese and Korean heritage earned higher wages on average than white workers and workers with Filipino, Vietnamese and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) heritage. Despite the high earnings of these groups, large wage disparities exist between women and men, with male workers with Asian Indian heritage making 32.7% more than female workers with Asian Indian heritage, male workers with Chinese heritage making 19.9% more than female workers with Chinese heritage, male workers with Japanese heritage making 28% more than female workers with Japanese heritage and male workers with Korean heritage making 25.3% more than female workers with Korean heritage.

Wages for workers with Filipino, Vietnamese and NHPI heritage remain low in Washington State. Males with NHPI heritage make $59,330 on average, while women make $44,937. Male workers with Vietnamese heritage make $75,636 on average, while female workers make $54,335. Male workers with Filipino heritage make $60,690 on average and female workers make $61,. This compares to the average earnings of white men making $93,194 and white women making $66,491.

While some Asian American populations earn higher wages on average, Asian American individuals are more likely to be in poverty than white individuals. Asian Americans have a poverty rate of 9.3% and NHPIs have a poverty rate of 15.3%. This compares to the 8.1% poverty rate of white individuals. In Clark County, and individuals with AANHPI heritage are more likely to qualify for free lunch, with 11% of individuals with Asian heritage and 19.9% of individuals with NHPI heritage qualify, compared to the overall qualification of 9.2%. Combatting these disparities will require a concerted effort from a variety of organizations, businesses and government.

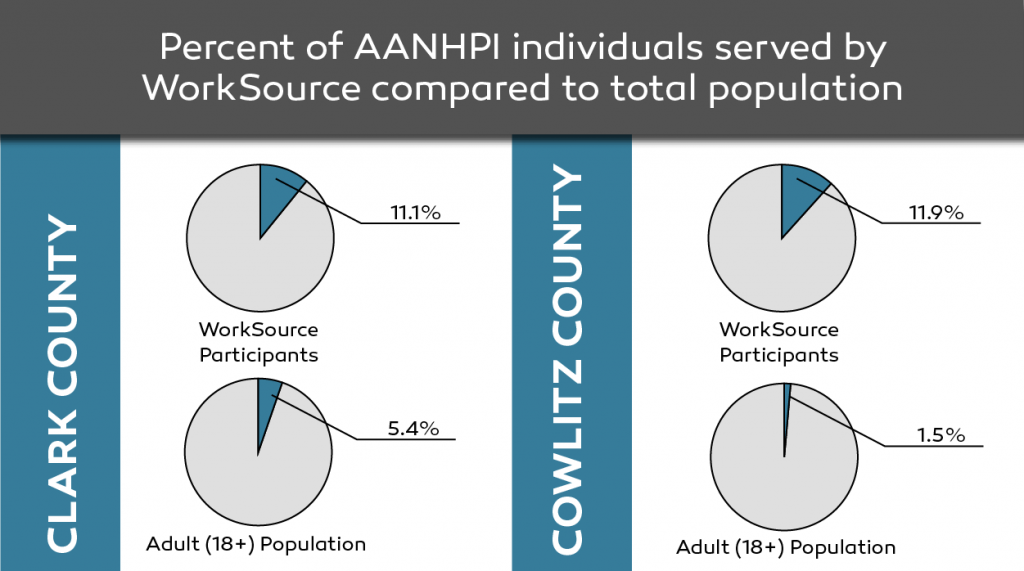

Workforce Southwest Washington (WSW) invests in adult career and employment services through two WorkSource centers. Of the participants served at WorkSource in Clark County during 2020-2021, approximately 11.1% (174 participants) were individuals with AANHPI heritage. Comparatively, individuals with AANHPI heritage represent 5.4% of the total adult (18+) population in Clark County. That individuals of AANHPI heritage are needing public workforce system services at a larger percentage than their representation in the region’s population suggests a need for increased economic opportunity, career services and resources.

Workforce Southwest Washington (WSW) invests in adult career and employment services through two WorkSource centers. Of the participants served at WorkSource in Clark County during 2020-2021, approximately 11.1% (174 participants) were individuals with AANHPI heritage. Comparatively, individuals with AANHPI heritage represent 5.4% of the total adult (18+) population in Clark County. That individuals of AANHPI heritage are needing public workforce system services at a larger percentage than their representation in the region’s population suggests a need for increased economic opportunity, career services and resources.

At WorkSource Cowlitz/Wahkiakum 11.9% (42) of participants served were of AANHPI heritage. WSW’s Economic Security for All grant designed to help residents in South Kelso and The Highlands in Longview move out of poverty served 10.3% (17 participants) of populations with AANHPI heritage of a total 165 participants. In Cowlitz County individuals with AANHPI heritage make up 1.5% of the total adult population and 1.9% in Wahkiakum County.

Through location-based services, focused outreach and customer-centric program design, WorkSource has been successful in serving AANHPI populations at a rate higher than the group’s population make-up in the three counties served.

In addition, WorkSource and WSW’s Next youth career center offer translation services to ensure that individuals without English proficiency are able to access and receive quality employment services across the region.

To help create our vision of a region where economic prosperity and growth exists for every person, WSW continues to evaluate our investments, tailor programs and services and prioritize the needs of historically excluded or underserved populations. Our grants for employee training prioritize workplace equity and require businesses that apply have at least 20% of employees from historically-excluded communities.

Our Job Seeker Services Request for Proposals (RFP), released in January 2022, took a new investment approach and aimed to increase accessibility and strengthen WSW’s commitment to inclusion and equity by utilizing a population-specific co-investment strategy to serve people where they are and create community ownership and a greater representation of the region’s diverse communities.

Adult job seekers should contact WorkSource Vancouver at 360.735.5000 or drop-in at 204 SE Stonemill Drive, Suite 215, Vancouver, WA 98684 or contact WorkSource Cowlitz/Wahkiakum at 360.577.2250 or visit 305 S Pacific Avenue, Suite 101, Kelso, WA 98626.

Young adult job seekers (ages 16 – 24) should contact Next at 360.207.2628 or email Next at admin@nextsuccess.

For businesses seeking training opportunities, help with employee recruitment and retention or industry-specific supports contact WSW’s business team by submitting a business request.